Just visited my old stomping grounds in Moab, Utah, pop. 5,200. A uranium town, adventure sport hub and now second-home magnet, this joyous mash-up of rednecks, hippies and everyone in between has boomed and busted repeatedly. It’s now at risk of becoming a municipal cautionary tale.

After years of gradual change, 2014-17 saw monstrous growth, and I use the adjective advisedly. The newest half of the 20-odd motels lining Main Street ignore local character and have no provision for staff accommodation, in a region where a cleaner’s one-way commute can be above 180km. The explosion of road-legal 4x4s called Razrs has meant this formerly seasonal town is now rammed 9-10 months of the year and rental homes are sprouting like mushrooms. Rooms are renting for US$600-800 each and the median home price is US$355,000. Median household income is US$41,500, but the bulk of jobs are at or below minimum wage.

The construction mini-boom is all by the book, which is part of the problem. With one trained planner and a five-person planning commission v. an ardent and noisy pro-development lobby, city planning can barely keep up with applications and enforcement, and has no scope for strategy or policy review. (Their third agenda item for 22nd Feb is “Updated list of barriers to affordable housing”.)

Like all American municipalities, Moab operates on zoning (Wiki primer here) – the system has lots of fans because of its simplicity, but in resource-strapped towns like this one, zoning can be seriously out of date and no longer fit for purpose. And while zoning allows for variances, there is no scheme-by-scheme negotiation as in the UK, and there is usually no affordable housing requirement for new development. In a town where the bulk of employment is low-paid tourism work, that is massively counter-productive.

This is also high desert, where precipitation is tracked religiously and running out of water is not an idle threat (viz Cape Town, SA). Moab caps an 18-mile-long valley, the southern half of which is in an adjacent county not known for planning or environmental restraint. San Juan County wants another 5,000 homes at that end of the valley – doubling the area population. While the county promises a new reservoir and infrastructure provision, any water or sewer failure is likely to be blamed on Moab, which will be the new subdivision’s services hub.

There is also a lot to be admired here (aside from the national and state parks, wilderness trails and snow-capped mountains at its doorstep). Moab City is home to the Best Small Library in America (2007), lovely bike paths, new schools and sports facilities, geothermal heating for municipal buildings, strong community and recycling support and a disproportionately large Pride festival; it has not forgotten locals in the scramble for tourist dollars.

There is also a lot to be admired here (aside from the national and state parks, wilderness trails and snow-capped mountains at its doorstep). Moab City is home to the Best Small Library in America (2007), lovely bike paths, new schools and sports facilities, geothermal heating for municipal buildings, strong community and recycling support and a disproportionately large Pride festival; it has not forgotten locals in the scramble for tourist dollars.

Much of the town’s success is due to leadership: it had a hugely progressive city manager for 21 years, and its new and equally forward-thinking manager, formerly Chief of Staff for Salt Lake City, is focused on strategy over catch-up. The City also seems to be getting along better with the surrounding and much more traditional Grand County, but time will tell.

Moab’s resilience is also due to the entrepreneurial and sometimes anarchic attitude locals and ‘seasonals’ – especially boating, biking and climbing guides – have about helping each other. Events like the Trashion Show raise funds for recycling, and landowners house needy kindred spirits in anything they can lay their hands on. Moab Valley now feels like a cross between (old-school) Burning Man and Pleasantville – not home to me any more, but still working for a lot of people.

Does this microcosm of tourism and development have any lessons for London and/or other places in the UK? Aside from the above about leadership and the long view, we could learn from them and pursue a tourism or transient room tax of some kind to mitigate the burden visitors place on infrastructure (and our patience!). We can also take heart that for all its shortcomings, we are actively working on the relationship between jobs and housing, on improving the environment, and on allowing room for the kind of entrepreneurial spirit that thrives in these weird and wonderful places.

This post first appeared at www.futureoflondon.org.uk

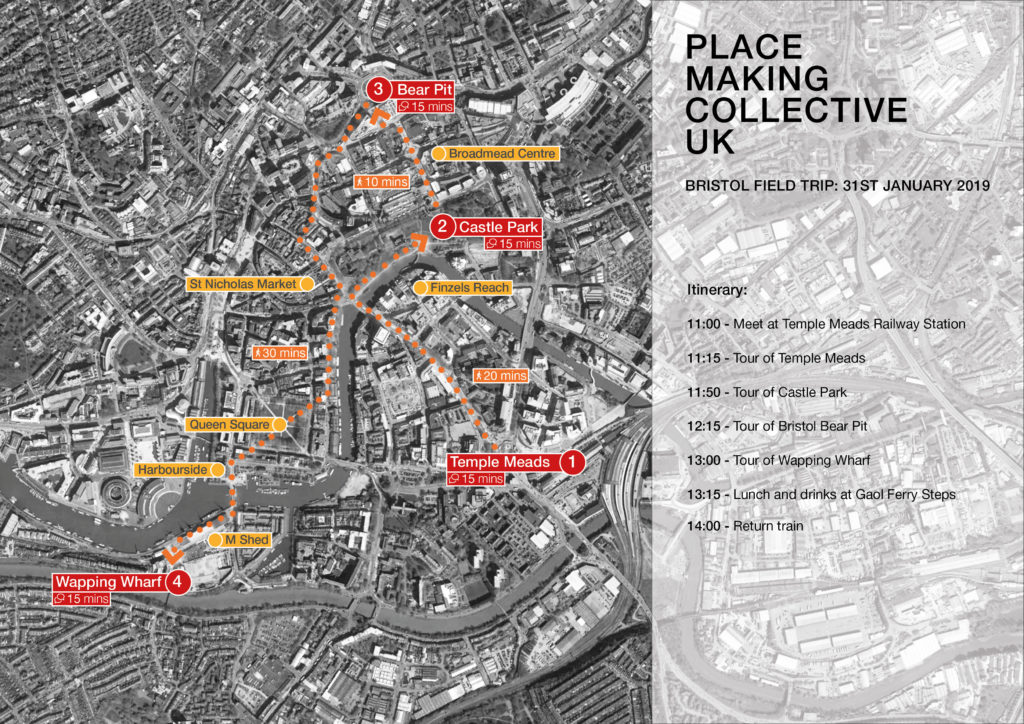

To outsiders, Bristol’s

To outsiders, Bristol’s

The last stop on the trip, Wapping Wharf and Gaol Steps, could be seen as typical hipster gentrification – or as a step in the right direction. The mixed-use development will provide 38% technically affordable homes mixed in with market sale property, shops, restaurants, shared workspace and access to the water on both sides. It’s an attractive place, and clearly adds to the city’s offer. Is it an exemplar for the new One City Plan? It will be interesting to hear what plan leaders say.

The last stop on the trip, Wapping Wharf and Gaol Steps, could be seen as typical hipster gentrification – or as a step in the right direction. The mixed-use development will provide 38% technically affordable homes mixed in with market sale property, shops, restaurants, shared workspace and access to the water on both sides. It’s an attractive place, and clearly adds to the city’s offer. Is it an exemplar for the new One City Plan? It will be interesting to hear what plan leaders say.