This post also appears at Future of London (my sometime other hat). You can find links to key FoL research below.

This post updates some of the findings in FoL’s Paying for Public Projects briefing, the product of three late-2019 roundtables and further research by 2016-20 Head of Knowledge Amanda Robinson. The programme was supported by Montagu Evans, Poly Group and Lewis Silkin.

Get ready to flex. Over the last 10 years, housing, infrastructure and regeneration delivery has been moulded by austerity and political flux; all sectors responded as well as they could. In the last three years, add the tragedy and deep impacts of Grenfell; climate declarations & court decisions; Brexit (remember that?); and now Covid-19, with its awful death toll, its policy and fiscal upheaval, and its economic ravages.

London’s incandescent glow was also starting to fade a bit before the pandemic, with medium-term value growth in the housing market forecast well below other regions and a cooler reception from central government as part of regional ‘levelling up’. That may seem fair in a national context, but it doesn’t help get projects funded.

Through it all, public project leads from all sectors have had to secure finance for upfront costs and funding for operations and maintenance. Budget cuts and housing policy were already pushing the public sector to risk more via joint ventures and council building programmes. Housing associations – partly in response to grant cuts and rent caps – reviewed activity, assets and tenure, embraced shared ownership; merged and morphed; and ventured into modular construction.

For councils in particular, finance has been a rollercoaster: removing the cap on Housing Revenue Account borrowing freed their aspirations; a year later, the 1% hike in Public Works Loan Board interest rates – partly in shock (…) at borrowing levels – slapped the curb back on and sent projects across the country reeling.

We will also lose EU funding – the Structural & Investment Fund alone is worth £5.3bn to England – but the replacement UK Shared Prosperity Fund is not yet defined and could be eroded by the flood of Covid-19 emergency spending.

To assemble finance and funding packages (and critical support), organisations of all kinds have been partnering more – from multinational masterplan partnerships to regional and local projects relying as much on social as on financial capital.

The fitness of other options, including municipal bonds, institutional investment and bank loans, will become clearer over the coming 6-12 months as the UK emerges from lockdown and assesses the economic damage.

Unfortunately, there’s a constant through all of this: a shortage of skills, capacity and understanding.

Whatever the tools, public project leads – especially at councils – can lack expertise, experience or just the time and headcount for effective funding and finance. Across the table, many investor and development partners still don’t understand the political or process realities of public delivery. Housing associations have been able to hire – though watch for the pandemic’s budget impact – but are increasingly challenged on ‘mission’. Having cash doesn’t mean the pressure is off.

Paying for Public Projects report

Early in 2020, Future of London combined its own research on the above with insight gained from three senior roundtables to produce a briefing on trends, risks and opportunities: Paying for Public Projects.

Supported by partners Montagu Evans, Poly Group and Lewis Silkin, the programme was designed to build public sector knowledge of funding sources and to help delivery teams and funders appreciate each other’s drivers and constraints. Covid fallout may shift the dial on best-fit funding, but the principles hold true.

The report provides cases and resources on trends including:

- Investment shifting from inner to outer London. From 2015/16 to 2018/19, housing starts in inner London dropped by 57% while outer London marginally increased[1].

- Investors attracted to assets offering revenue-generating potential and longer-term capital gains[2].

- Climate issues affecting investor attitudes. Some are divesting from fossil fuels and applying ‘temperature scores’ to grade their portfolios[3]. Others heard the Court of Appeal decision against Heathrow expansion with trepidation. It’s under appeal, but it was a marker.

“Montagu Evans was delighted to support this programme,” writes partner Oliver Maury. “In the context of Covid-19 and its impact on society, our ability to share knowledge and experiences, in this case in relation to the funding of public projects, is more important than ever. As society turns its attention towards the recovery phase, we see organisations like ourselves and Future of London having an important part to play.”

So how can public project leads respond now?

There are still opportunities for public project funding – some perhaps growing as priorities shift…

- A stronger emphasis on placemaking has been creating more resilient neighbourhoods that build on local identity and respond to local need. This strategic approach to regeneration demonstrates public sector leadership, which in turn inspires investor confidence. What happens now, as battered small businesses struggle to recover or leave shops vacant, is critical – council and landlord actions and attitudes are key to sustainability in every sense.

- Emphasising – and clearly defining! – social & environmental value are likely to become more of a factor, as are explicit community support and mandates such as estate regeneration ballots. Because of their responsibility to communities, public-sector organisations are more likely to call for projects that maximise these values – and attract the growing number of investors with similar ambitions (viz the rise of Environmental, Social & Governance or ESG investing).

- Good asset management is linked to both of the above. Rather than selling off, local authorities and housing associations are using mechanisms like income strips[4] to retain control of assets and explore income-generating opportunities as landlords. Again, they need the skills to do this well and the resources to scan the horizon for risks and opportunities post-Covid.

- In London, engage with the Mayor’s Good Growth theme, with funds and support for projects offering the above and/or citizen engagement and diversified local economies.

- Look to outer boroughs: There was already a huge amount to do in Outer London – and outside the centres of most UK city-regions – as town centres and high streets struggled to evolve. There will be ten times more to do now that they risk being hollowed out – and there will be public and private money ready to invest. What is brought back or built will be critical.

- “Be shovel-ready”: This from a Leaders Plus candidate in Greater Manchester, but applicable anywhere. The UK will emerge and central government – from Homes England to the Department for Transport – will spend to help rebuild the economy. Moving ahead with deals, design, planning, consultation and procurement will help capable entities stand out when those initiatives kick in.

How do we look further ahead?

Scan. Listen. Learn. Collaborate. Flex.

Stability is never permanent, and the funding landscape will continue to shift. A key takeaway from the last 10 years was that local authorities must be more resilient when it comes to economic shocks. A key takeaway from the last two months is that central government will spend in a crisis. It remains to be seen whether that means a revolution in fiscal policy – with a return to serious housing and care funding, for example – or it means the cost of repayment will drive councils further into the red. What can we do to prepare?

Scan: Public project leads need to understand what funding sources are available, which are emerging, which are safe, and who’s using what. Carve out time for your team to scan good publications – or commission summaries if you have the budget. Room 151 is good.

Listen: Talk with colleagues beyond your organisation, via Future of London, professional groups and live or online networking events. Mentoring and board service across sectors or disciplines are great ways to do this.

Learn: Take courses, read the FT, Economist or HBR, listen to brain-stretching podcasts. Look at successes and failures and go beyond the gossip to what actually happened. Take your CFO for a coffee and ask how things work!

Collaborate: Work with each other. Share knowledge. Share people via secondments. Try using consortia once in a while to keep things fresh. Do a project or have a meeting with a competitor.

Flex: Doing the above, using tools like Future of London’s report and wider network – and having trusted outside help where warranted – can give public sector officers the confidence to take on risk and make fresh decisions. At the same time, those practices can help savvy private-sector operators understand partners and clients better, and by extension help repair public trust in the development and regeneration process.

FoL’s Paying for Public Projects programme brought together cross-sector development, housing, regeneration and funding partners to help build mutual understanding. In 2020, FoL is set to launch a new training programme for public project managers. These courses will be designed to help practitioners enhance their commercial skills by learning about viability, asset management, contracts and negotiation. Find out more here, or contact FoL Chief Executive Nicola Mathers at nicola@futureoflondon.org.uk.

Download the full Paying for Public Projects report here.

Get involved with Future of London’s useful work and excellent 4,600-strong network here.

Footnotes

- MHCLG Table 253: permanent dwellings started and completed, by tenure and district. Inner/outer London definitions follow those used in the London Plan. Some figures imputed by MHCLG in the data table. bit.ly/32d7gyj

- Hugo James. “The rise of long income property as an asset class,” 15 Jan 2020. www.investmenteurope.net/opinion/4009153/rise-long-income-property-asset-class

- Simon Jessop, Matthew Green; Reuters. “Climate change pushes investors to take their temperature,” 20 Jan 2010. reut.rs/2V9PFFU

- Clive Pearce. “Freeths Real Estate Law Blog: Income Strip Leases,” 5 Sep 2019. www.freeths.co.uk/2019/09/05/income-strip-leases/

There is also a lot to be admired here (aside from the national and state parks, wilderness trails and snow-capped mountains at its doorstep). Moab City is home to

There is also a lot to be admired here (aside from the national and state parks, wilderness trails and snow-capped mountains at its doorstep). Moab City is home to

To outsiders, Bristol’s

To outsiders, Bristol’s

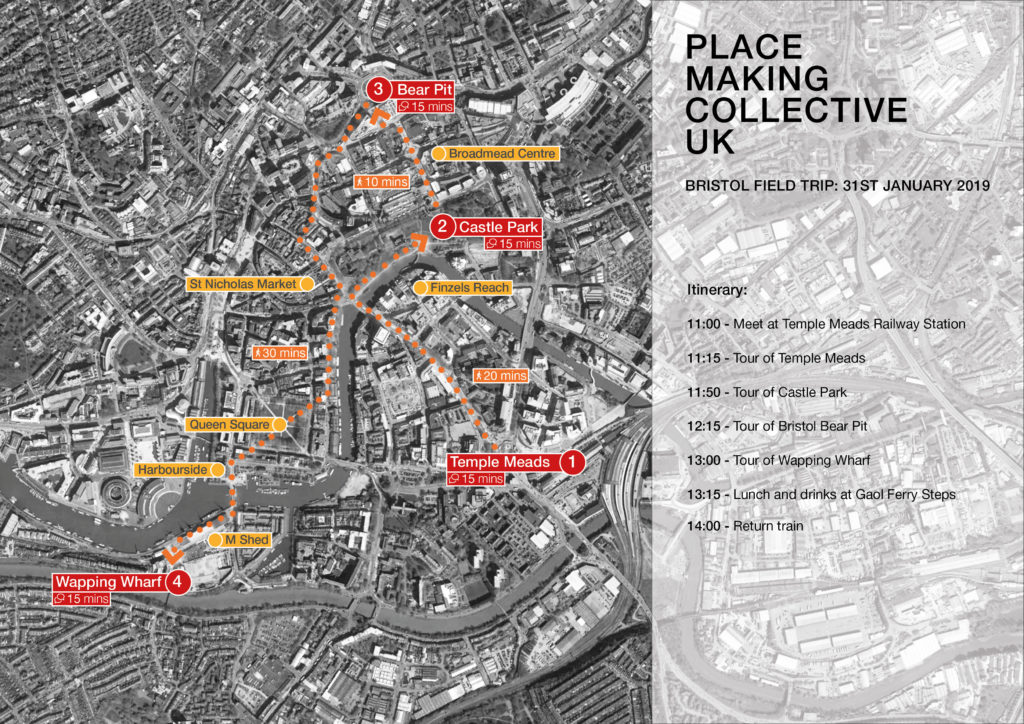

The last stop on the trip, Wapping Wharf and Gaol Steps, could be seen as typical hipster gentrification – or as a step in the right direction. The mixed-use development will provide 38% technically affordable homes mixed in with market sale property, shops, restaurants, shared workspace and access to the water on both sides. It’s an attractive place, and clearly adds to the city’s offer. Is it an exemplar for the new One City Plan? It will be interesting to hear what plan leaders say.

The last stop on the trip, Wapping Wharf and Gaol Steps, could be seen as typical hipster gentrification – or as a step in the right direction. The mixed-use development will provide 38% technically affordable homes mixed in with market sale property, shops, restaurants, shared workspace and access to the water on both sides. It’s an attractive place, and clearly adds to the city’s offer. Is it an exemplar for the new One City Plan? It will be interesting to hear what plan leaders say.